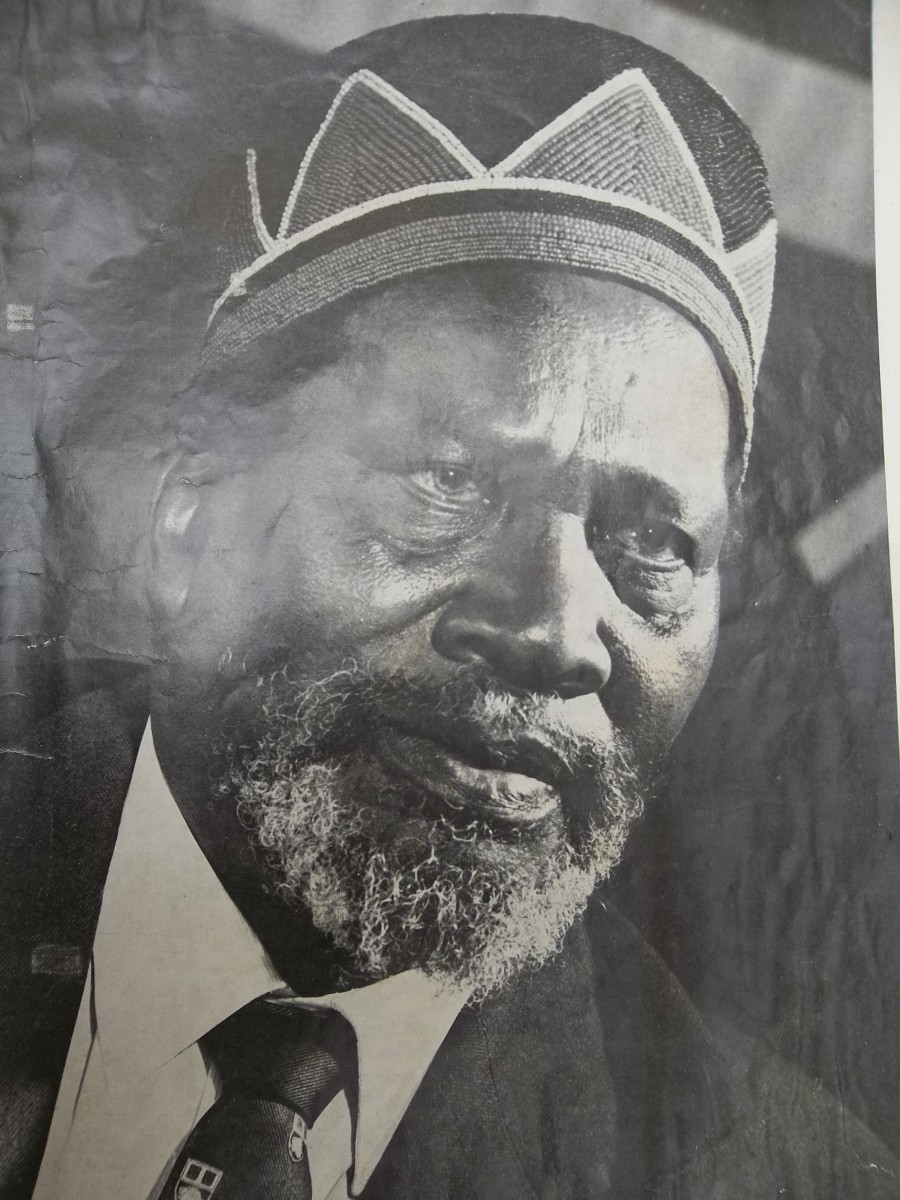

A Message to Kenyans from the Prime Minister, Jomo Kenyatta, at Kenya's Independence in 1963

Jomo Kenyatta's message in 1963

Jomo Kenyatta was the first president of the independent republic of Kenya. In anticipation of independence day, Kenyatta had this to say in a special issue of the Pan African magazine:

"December the 12th, 1963! This is the happiest, the most wonderful day in my life, the day our beloved Kenya becomes free.

It is a day which can come only once in a lifetime—the day when a lifetime’s effort is suddenly fulfilled.

For a moment, it is hard to believe that it is true. For this day has been won with such long effort, such sacrifices, such sufferings...

Now at last, we are all free, masters in our own land, masters of our destiny...FREE!

What shall be my message to readers of PAN AFRICA?

First, enjoy yourselves! Be happy! Breathe deeply this sweet, pure air of freedom! This freedom is your’s – your’s for the rest of your lives—to pass on to your children and your children’s children. Freedom! The most glorious blessing of mankind.

Let us share together this great day of joy.

Today, our national flag, the flag of free, independent Kenya, flies proudly, gaily in every corner of our land.

Today, we may stand in reverence to the music of our own national anthem.

These are the symbols of our hard-won rights. Treat them with respect. Honor them.

The second part of my message is this.

Treat this day with joy. Treat it also with reverence. For this is the day for which our martyrs died. Let us stand in silence and remember all those who suffered that our land might be free, but did not live to see its fulfillment. Let us remember their great faith, their abiding knowledge that the victory would be won.

We are like birds which have escaped from a cage. Our wings have cramped. For a while we must struggle to fly and regain our birthright for the free air.

We shall make our mistakes, but these will be only like the temporary flutterings of the escaped bird. Soon our wings will be strong, and we shall soar to greater and greater heights.

This freedom has not come easily. Nor must we expect the fruits of freedom to come easily.

This nation, Kenya, will be as great as its people make it. So I ask you to make this day of freedom a day of dedication.

I ask you to dedicate yourselves to the memory of those who have gone before us and to those who must follow us. I ask you to resolve to put aside all selfish desires and to strain every ounce of muscle and brain to building a nation which shall honour our dead, inspire our living and prove a proud heritage for those who are yet to come.

In the name of all these, HARAMBEE!

JOMO KENYATTA

A Brief History of Kenyatta's Struggle for the People of Kenya

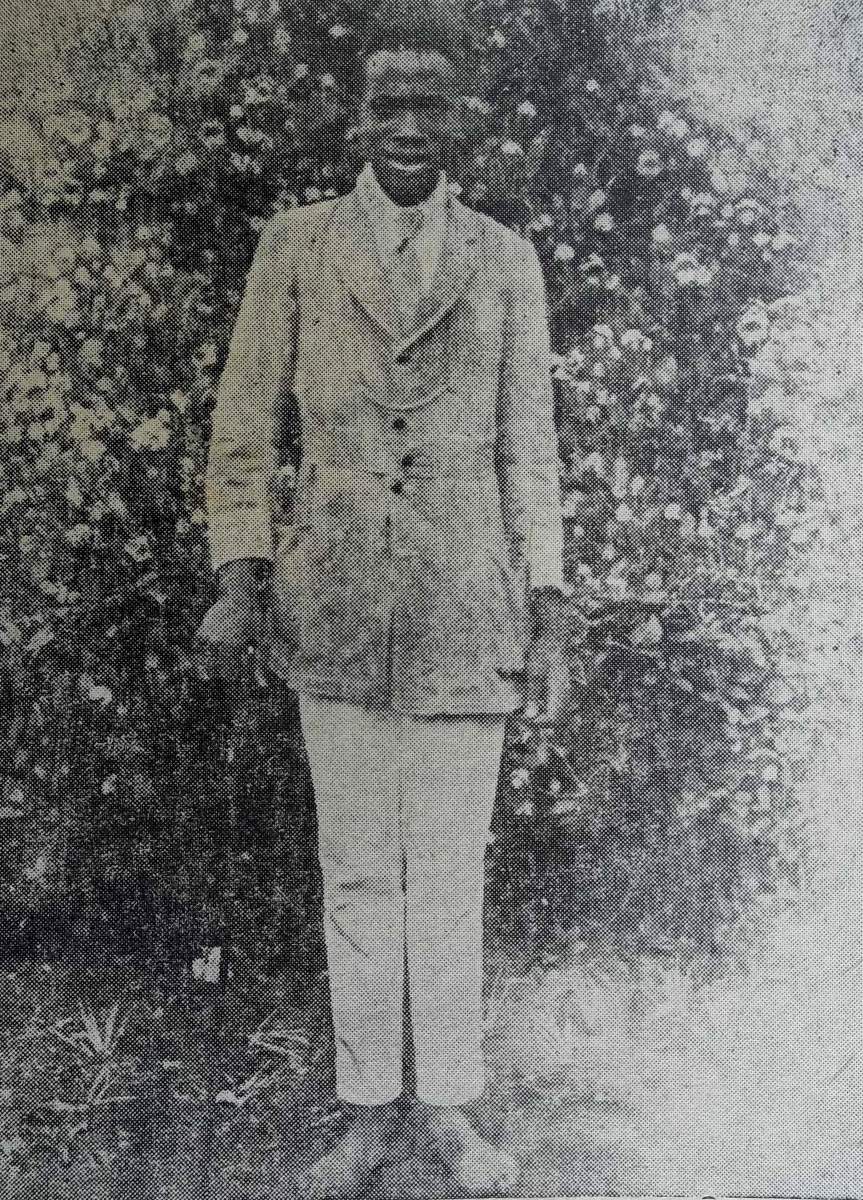

Kenyatta was born in the early 1890’s, a few years before the completion of the Uganda Railway from the port of Mombasa to port Florence on Lake Victoria. Kenyatta’s real name was Kamau. However, he changed it to Kenyatta when he came of age. It is not lost on the keen reader that the name Kenyatta has all the five letters that form the word Kenya. That the owner of such a name should become the first president of Kenya is a remarkable coincidence. Kenyatta’s real father died when he was very young, so his mother, Wambui, was ‘inherited’ by Kenyatta’s uncle Ngengi, as was the custom. That is how young Kamau came to be known as the son of Ngengi. Tragedy struck again when Kenyatta's mother, Wambui, died in childbirth. It would appear that Kenyatta's relationship with his stepfather was not ideal. Rather than stay with Ngengi, Kenyatta chose to migrate to his grandfather’s home in a place called Muthiga, a short distance from present-day Kikuyu township. From there, the allure of education in a missionary school was irresistible. Driven by this thirst, Kenyatta moved to Thogoto on his own accord, a short distance from Muthiga, for his desired knowledge. The institution, which had a church and school, belonged to the Church of Scotland mission. Kenyatta worked there as a cook to earn money for his education. The word Thogoto is actually a corruption of ‘Scotland’ by the Kikuyu, whose language replaces the letter ‘S’ with a ‘th’ sound. Kenyatta's earliest picture shows a barefooted young man of about 14 years of age, wearing a shirt, necktie, and an old-fashioned overcoat while holding tightly to a cane with his left hand. The allure of education was accompanied by a desire to be the perfect gentleman as well. The young man strikes a very confident pose, indeed.

After his education at the mission, where he also trained in carpentry besides English, reading, and writing, Kenyatta did several clerical jobs, including, at one time, reading water meters for the then small town of Nairobi.

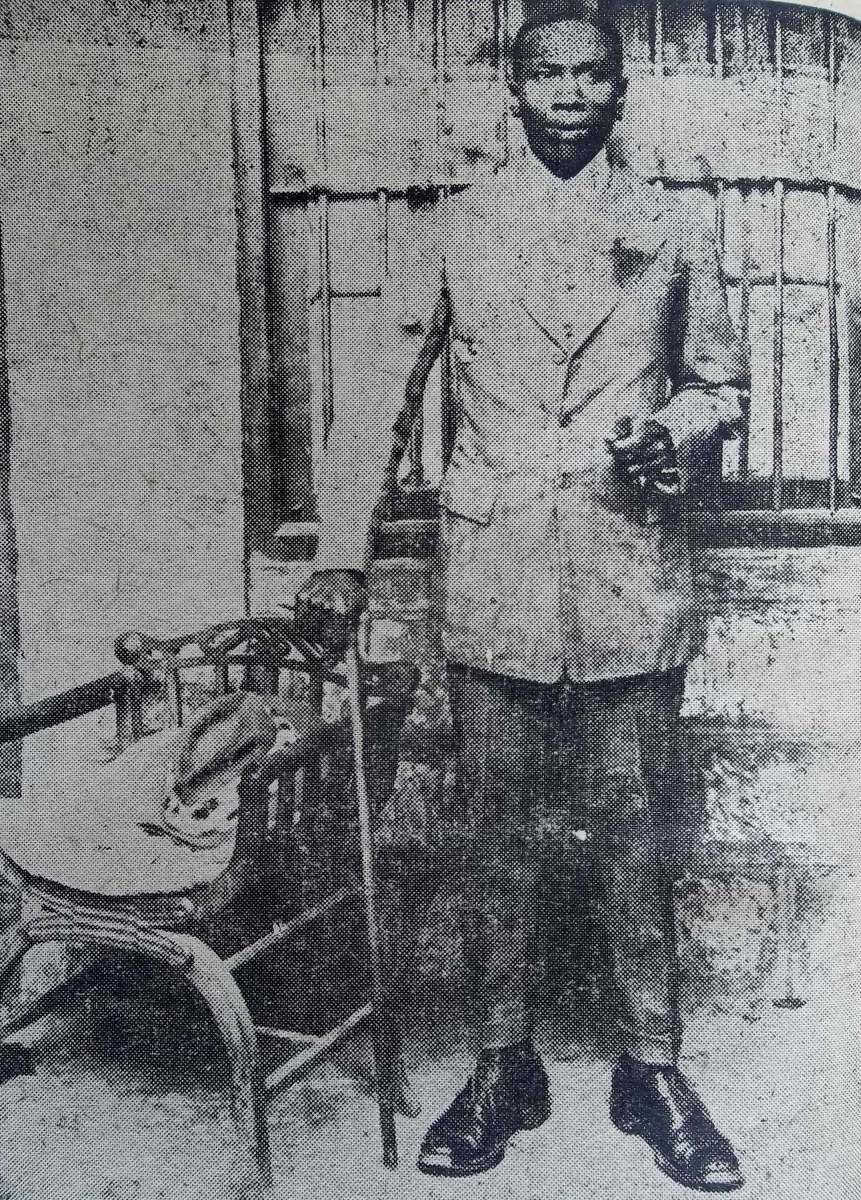

Barely four years after joining the Scotland Mission School at Thogoto, the same Kenyatta is photographed in better-fitting clothes, a suave young man, still with the gentleman's cane in his left hand, ready to conquer the world.

Later, Kenyatta married Wahu, with whom they had their first son, Peter Muigai Kenyatta.

Devide and Rule Tactics of the British Colonial Government

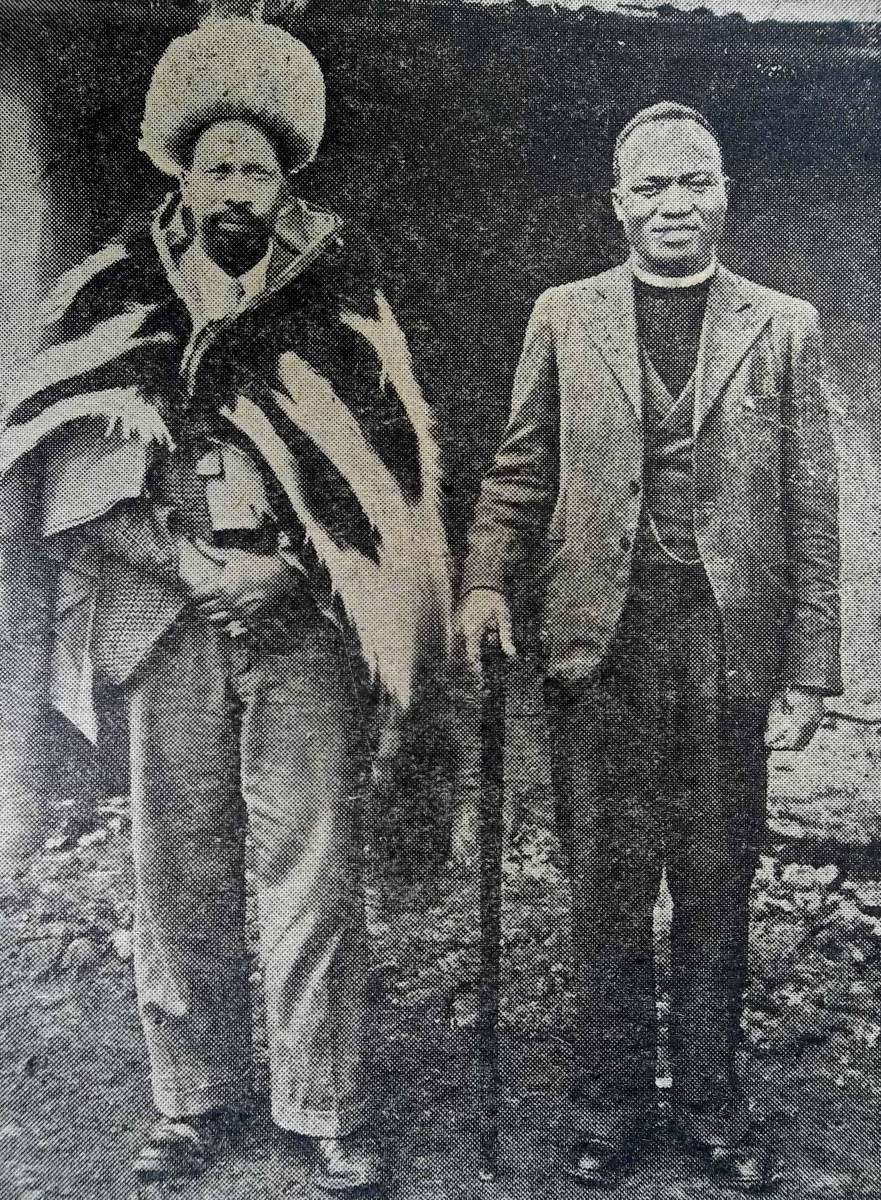

In a divide-and-rule tactic, the colonial government in 1923 allowed the formation of political parties as long as they were confined to single tribes and not a multi-ethnic membership. Kenyatta would later come into the picture to correct that injustice. This supposed magnanimity on the part of the government led to the formation of the Kikuyu Central Association, with Joseph Kangethe as president and Jesse Kariuki as his deputy. In 1926, Jomo Kenyatta was elected as the Secretary of KCA and soon after launched the Muigwithania (the mediator) magazine. From the title, one can deduce that the Kikuyu Central Association started right from the outset on a non-violent path.

Having received education through his efforts, Kenyatta understood quite early that only a European education would remove his people from poverty. In one of the issues, Kenyatta wrote that if the people wanted to develop, they ought to be:

“...industrious, trustworthy, patient, happy, and cooperate as Europeans do. An educated tribe or nation defeats an uneducated tribe or nation. You better swalow that...”

Kenyatta was particularly keen to understand the intricacies of the European way of life, and it cannot be by coincidence that in 1928, the Kikuyu Central Association sent him to Britain to represent African grievances to the British government. He was recalled in 1931 but was soon back in Britain in 1932, when the association appreciated the publicity he had generated. In his absence, George Kiringothi acted as the secretary. Kenyatta took advantage of his sojourn in Europe to undertake advanced studies at the London School of Economics. Kenyatta was to remain in Britain until 1946.

In 1940, the KCA was banned. The Settlers concocted an excuse that its members had made contact with the Italians, who were at the time enemies of the British Government. Upon its proscription, 22 Africans, among them James Beuttah, were arrested and, as was the practice, deported to various parts of the country until after the war in 1945.

The banning of the KCA meant that the Africans had lost a mouthpiece. Africans were still treated as fourth-class citizens, in spite of helping Britain in the war effort. Many had fought alongside British soldiers in Burma and the Middle East. Below are some of the issues that caused the most bitterness among the Africans:

- Loss of tribal land

- Discrimination based on color: they could not use ‘whites only hotels,’ buses, schools, or even toilets.

- Unequal pay in the civil service, regardless of the qualifications.

- Africans had been banned from growing cash crops reserved for Europeans only.

- No representation in the Legislative Council.

- The use of African reserves as reservoirs of cheap labor

When African lands were taken over by Europeans, the Africans became squarters on the same lands. Initially, the Europeans allowed them to stay on with their cattle and goats and even gave permission for small-scale subsistence farming. However, at the end of the world war, the settlers acquired cheap loans to mechanize their farming methods. This mechanization led to a desire to put more land under crops, much of which was already occupied by the quarters. The settlers, who now needed less farm labor than previously, sought to kick out as many squarters from these lands as they could. Many Africans had little choice but to move to the emerging towns in search of work. To quote Pio Gama Pinto, “Victory over fascism and victory for democracy had no meaning for him” (the African). Pio Gama Pinto was the first freedom fighter to be assassinated in independent Kenya, and the murder has never been solved. The man who served a thirty-year term for the homicide swore, even after he was pardoned and released, that he was just a scapegoat. He claimed that he had no knowledge of the assassination before he was picked up by Robert Shaw, a police reservist, and forced to sign a statement.

Massacre Outside the Norfolk Hotel, Nairobi

In 1919, Harry Thuku formed the East Africa Association as president, with Ismael Ithongo as treasurer. Harry Thuku wrote a petition to the British Government in protest of the Hut tax, alienation of African land, and forced labor. The colonial administration did not take that kindly. He was arrested on March 14, 1922, and held at a police station next to the Noforlk Hotel, where Central Police Station stands today. An agitated crowd formed to demand his release. When the chief secretary, Sir Charles Bowring, ignored their demands, a woman by the name of Mary Muthoni threatened to disrobe if men did nothing to rescue Harry Thuku. Her threat was an age-old Kikuyu curse that was bound to spur the men into action. Muthoni's incitement increased the men's agitation a notch higher, causing the fidgety police to open fire. The settlers in the Norforlk Hotel joined in the fray, and more than 30 men and women were killed by a volley of bullets. Following that massacre, the association was banned, and Harry Thuku was deported to Kismayu, in modern-day Somalia. He was released in 1931 with little determination left to fight for the rights of Africans.

Though Harry Thuku was part of the group that formed the Kenya African Study Union (KASU), he had lost the fire that had seen him sent to Kismayu. Other members of KASU were Mbiyu Koinange, James Gichuru, Albert Owino, Joseph Katithi, Tom Mbotela, James Beuttah, Harry Nungural, Fred Kubai, Jesse Kariuki, Francis Khamis, and Ambrose Ofafa. Harry Thuku, however, paid little interest in confronting the British Government, choosing instead to expend his energy on successful farming.

Political Groupings Come of Age in Kenya

In 1946, the Kenya African Study Union (KASU), which had been formed by Harry Thuku, changed its name to the Kenya African Union with the determination to break tribal barriers and unite all Africans. The office bearers were James Gichru, W.W.W. Awori, Francis Khamis, Fred Nganga, and Joseph Katithi. The Union started Sauti ya Mwafrika (Voice of the African), a Kiswahili weekly newspaper. KAU, in the same year of its inception, sent Gichuru and Awori to London to represent African grievances. For some reason, it was only Awori who managed to travel to London, where he met Jomo Kenyatta. Kenyatta was, at the time, keeping company with other African nationalists in a nascent pan-African movement. These were Namdi Azikiwe, Kwame Nkuruma, Professor Dubois, and George Padmore. This is the same year that Kenyatta returned to Kenya. The following year, he was elected president of KAU. Kenyatta must be credited with invigorating the party; membership grew, and meetings were held all over the country. Many Africans who had fought for the British in Burma and the Middle East joined the party. This vogour must have sent jitters among the colonialists.

Kenyatta held meetings all over the country to explain what KAU stood for. In one of his forays into Western Kenya, he met Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, who was the leader of Luo Thrift Corporation, with Achieng Oneko as the secretary and editor of Ramogi. The zest in KAU had a magnetic effect on both of them. Ramogi soon joined KAU and was rewarded with the post of secretary, while Oginga served on the Central Committee and Governing Council.

Nervous about the increasing strength and popularity of nationalist movements such as KAU, the colonial administration embarked on a strategy to neutralize the nationalists by arresting their leaders on 'trumped-up charges.’

The Maumau Uprising

More victims of the colonial strategy of detentions were Jesse Kariuki, detained for 11 years, and 80-year-old ex-senior Chief Koinange on a false charge of the murder of the puppet Chief Waruhiu. Though Koinange and his son Mbiyu were found innocent, the senior Koinange was detained far from home and only returned when his death was deamed imminent.

In 1949, a retired Kenya African Rifles soldier by the name of Meinertzhagen received reports from his loyal Kikuyu contacts that a secret society by the name of 'Maw Maw' was in the final stages of planning violent raids on the settlers. Meinertzhergen passed on the information to the authorities, but it was ignored. Perhaps this was the earliest mention of the Mau Mau rebellion. When the Mau Mau eventually struck with deadly consequences, they caused much terror to the settler community, the loyal African chiefs, and the British Government. Sir Evelyn Barring declared a state of emergency in 1952 and called in the British army to stamp out the rebellion. The small matter of the Mau Mau took more than five years to slow down.

The non-violent KAU was not cowed by the administration's repressive strategy. On the contrary, meetings continued country-wide, attracting up to “...thirty thousand people, and the money collected at these meetings was sometimes in excess of £1000 at each rally.” In these meetings, Kenyatta preached a non-violent doctrine, cautioning the crowds against being incited to violence by the settler community to avoid more arrests of African leaders. The colonial administration was not deterred from further arrests, and Jomo Kenyatta, together with five others—Achieng Oneko, Paul Ngei, Fred Kubai, Bildad Kagia, and Kungu Karumba—were arrested. That is when the colonial administration, seeing that Kenyatta was a formidable leader, falsely accused him of managing the Mau Mau rebellion and arrested him.

The Colonial government added the 4th Uganda Battalion of the Kings African Rifles and the Lancashire Fusiliers from London to fight the Mau Mau. “Over 2000 Europeans joined the Kenya Police Reserve.” A special force was brought in from the Northern Frontier District (NFD) to terrorize the African population in Kiambu, Fort Hall (Murang'a), Embu, and Nyeri. This force was notorious for beating Africans in the reserves, pillaging, looting the homes of detained persons, and raping women.

With its formidable asernal, the government launched “Operation Jock Stock,” whose major objective was to arrest all African nationalists, including leaders of independent schools and churches. Many were served with “Governors Detention Orders,” which included deportation or restriction without trial. With the KAU executives under arrest, the union fell into the hands of Walter Odede, Joseph Murumbi, and W. W. W. Awori. These three started to plan the defense of Jomo Kenyatta at the infamous Kapenguria Trial. They put together a battery of lawyers led by D. N. Pritt QC., H. O. Davies for Nigeria, Diwan Chamanlal from India, A. R. Kapila from Kenya, F. R. S. de Souza, and Jaswant Singh. More lawyers from Ghana, Nigeria, Sudan, and India had offered to join the team, but the government refused, perhaps due to the international interest that the case had attracted.

To secure a conviction in the Kapenguria trial of Jomo Kenyatta and his colleagues, the government used what has been described as “chicanery and subterfuge.” This included coaching witnesses with offers for rewards.

In the selection of a judge, the government did a good job for itself by getting a vengeful and prejudiced retired man in dire need of the remuneration that was offered for the job. He was Justice R. H. Thacker. For a witness, the prosecutor relied mainly on the evidence of a man described by Pio Gama Pinto as “...an unprincipled scoundrel by the name of Rawson Macharia.” Macharia was later to admit that he had given false evidence, which was mainly relied on to convict Kenyatta. Rawson revealed that he had been promised, “

(a) an air passage to the United Kingdom at £278.

(b) a two-year's course in local government at a university for £1,000.

(c) subsitence stipend for two years at £250."

In spite of his great help in the accomplishment of a conviction for the Colonial Government, Macharia’s later confession took him through the impressive British justice system for perjury. He was found guilty and jailed. It seems unlikely that he ever got his rewards.

The government went on a newspapers banning spree and arrested people en masse. “By October 31st, arrests in Nairobi totaled 2,309, Rift Valley 700, Central Province 561, and Nyanza 36.” This show of force gave the Colonial administration a false sense of achievement and security.

Judge's Comment at Kenyatta's Trial

“Although my finding of fact means that I disbelieve ten witnesses for the defense and believe one witness for the prosecution, I have no hesitation whatever in doing so. The prosecution witness, Rawson Macharia, gave his evidence well and, in my opinion, truthfully....all the defense witnesses were evasive, and I am satisfied, were not telling the truth. I therefore find as fact that Kenyatta was present at a ceremony of oath-taking, that he administered the oath....to two people and endeavored to administer it to Rawson Macharia.”

The Winds of Change in the British Empire

By 1957, the European settler hardliners had come to the realization that they could not continue to hold on to power against the wishes of a much more enlightened African population. They sought, however, to delay independence for Kenya by working with'moderate' Africans while at the same time ensuring that the difficult types like Jomo Kenyatta remained in detention and restriction. The small tribes were incited to fear domination by the big tribes. They were encouraged to form their own parties to fight for their rights, including a right to self-governance in a federal system yet to be debated, known then as Majimbo.

Some of the political organizations that appeared instantly were:

- Nairobi African District Congress

- Nairobi People's Convention Party

- Baringo Independence Party

- Central Nyanza District Congress

- Mombasa African Democratic Union

It is under these circumstances that the Lancanster House Conference was convened in England. Each district was to be a county, headed by a president. The colonial government aimed to make the formation of a unified government most difficult and thereby delay Kenya’s independence. Pinto had these to say about the prevailing situation at the time:

"The imperialist press in Kenya and European politicians were quick to seize the opportunity to excite tribal animosities to the maximum, and every report which helped to inflame tribal feelings found a suitable place in the European-controlled press."

The First Lancaster House Conference was held in January and February of 1960. Ronald Ngala was elected chairman. Under his leadership, the group, in spite of its diversity in composition, voted to fight for the release of all detained and restricted persons, one of whom was Jomo Kenyatta and ending the state of emergency that had been declared eight years earlier. They also resolved to unify the various political groupings under one party and relayed the information to the African leaders in Kenya for implementation. This placed Kenya firmly on the road to independence.

On March 27th, 1960, a meeting was held in Kiambu. The objective was to implement the resolutions of the London meeting and to unify the political groupings. Daniel T. Moi, Masinde Muliro, and Ronald Ngala boycotted the meeting, but Taita Toweet showed up briefly and then walked away. It had appeared at first as though the forces against the unity of the Africans would win.

The Kiambu meeting continued for two days, leading to the formation of the Kenya African National Union (KANU). Jomo Kenyatta, who was still under restriction in the arid town of Lodwar, was unanimously elected president in absentia. But the colonial administration would not register a party with Kenyatta's name as president. James Gichuru, who had been elected acting president, put his name on paper as president, and it was only then that it was registered. Jaramogi Oginga was elected vice president; Tom Mboya was the general secretary; Ronald Ngala was treasurer; Daniel was assistant treasurer; and Arthur Ochwada was assistant secretary. The idea was for all tribal and district political organizations to be dissolved and their assets to be transferred to KANU. Instead, under instigation from colonial conspirators, the Kalenjin, Maasai, Luhya, and coastal people formed their own party, the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU). The colonial government, under direction from the settler community, actively worked for KADU, which was seen as more pliable, hoping that KADU would win elections and lead a puppet government. KADU reciprocated by accommodating the so-called moderate whites.

In spite of all these machinations, elections were held. In 1961, the two main parties, KADU and KANU, pitted against each other. KANU won with a substantial majority but, under the instigation of Jaramogi Oginga, declined to form a government unless Jomo Kenyatta, its de facto leader, was released.

The state of emergency was ended on January 12th, 1960, but Kenyatta’s restriction and the detention of many others were continued. To ensure that KADU formed the government, Ngala and some of his colleagues were enticed by the Governor, Sir Michael Blundell, to cross over to KADU, and with the formation of several nominated seats, an unrepresentative government was formed.

KANU continued to excite crowds around the country, agitating for the release of Jomo Kenyatta. Passions ran high, and the colonial government, unsure of the outcome, moved Kenyatta from Lodwar to Maralal. In a bid to massage Ngala’s ego, an operation by the name “Miltown” was mounted, which led to the arrest of “over a hundred persons” who were detained without trial for supposedly endangering the life of Ronald Ngala.

Agitation over Jomo Kenyatta’s release continued, eventually bearing fruit on August 15, 1961, when he was transferred to his home in Kiambu. His detention was officially revoked on Tuesday, August 21st, at 9 a.m. This opened a floodgate of visitors from all walks of life, by any means possible, much to the chagrin of the colonial administration, which had implied that he was too old, perhaps even senile, to lead an independent nation. Kenyatta's eloquent speeches left no doubt that he was indeed in tune with the national and international issues of the time. In the meantime, the government continued with its futile attempts to flatter KADU members, besides fueling animosities between the so-called small tribes and big tribes.

Newsreel on Kenyatta, 1973

Kanu Elections, 1963

When the next KANU elections were held, Kenyatta was elected unopposed, putting him at the helm of leadership in the second Lancaster House Conference to discuss the Independence Constitution.

General elections were held in May 1963, and KANU had an overwhelming majority of 72 seats out of the available 112. KANU also gained from some defections, which further increased the seats to 92 against KADU’s 31.

On June 1, 1963, the colonial government allowed Kenya ‘internal self-government' with Jomo Kenyatta as prime minister. The government was still firmly in the hands of the governor on behalf of the Queen of England. Kenyans did not want that arrangement to remain for long, as had happened in some British dominions where partially independent states still owed allegiance to the Queen of England. Such states had the Union Jack embedded in a corner of their flags.

Kenyatta immediately sought his East African counterparts, Julius Nyerere of Tanganyika and Milton Obote of Uganda, with the proposal to form an East African Federation. This dream led to the formation of the East African Common Services Organization, which later changed to be the East African Community. Among the common services were East African Railways and Harbours and East African Airways. The East African Community survived up to the 1970s, when ideological differences between Kenya and Tanzania and the emergence of Idi Amin Dada after the overthrow of Obote in Uganda made further cooperation impossible.

Fifty years later, Kenyatta's own son, Uhuru, was the president and commander in chief of the armed forces. Uhuru was so named for having been born during the euphoria that came with independence—Uhuru in Kiswahili.

Uhuru Kenyatta was the fourth president after Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi (who took over in 1978 when Jomo Kenyatta died) and Emilio Mwai Kibaki, who took over from Moi when multiparty politics were allowed again in 2002. Uhuru came to power after the elections of March 3rd, 2013 under a new constitution that echoes the sentiments of the Majimboists of 1960.

The Kenyatta Presidency

A quotation from Kenyatta - 1938

The Gikuyu have been able to record the time when Europeans introduced a number of maladies such as syphilis into Gikuyu country, for those initiated at the time when this disease first showed itself, are called gatego i.e. syphilis.

The Kenya National Anthem

The National Anthem was composed by a teacher, Meza Moraa Galana. He used a lullaby tune from his Pokomo community to create the memorable tune that is played all over the world when Kenyans win marathons and other international races. Meza was interviewed on November 4th on Citizen Television in 2013, aged 94.

The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Poorer

After independence, a new class of Kenyans was instantly created from the privileged few. Though the economy grew substantially, the gap between the rich and the poor continued to widen. Here is a poem by Emmanuel Kariuki about this development

A song of class

Ship them back,

To their one roomed rondavels,

All these pedestrians,

Who swam accident scenes,

Like flies to a carcas.

These unschooled judges,

Ignorant ignoramuses,

Of the Highway Code,

At the snap of a finger,

They know which driver is wrong.

Round them up,

All those idling vagrants,

Who dash from the sidewalks,

To stroll on the pedestrian crossings,

Sheer willing obstruction!

I caught one,

A really fat specimen,

Sitting on my Mercedes Benz!

Obviously a dependant,

Of a poor hard worker like me,

Scatter them all,

With tear gas canisters,

All those on-lookers who stare in awe

When our firms catch fire!

Only to scamper at the slightest explosion.

Stave them off,

These vehement criticisers

Of our panctual police and gallant firemen

Yet, shameless looters and pilferers

In the ashes, cinders and ruins.

Ship them back to their overcrowded villages,

To herd their scrawny humped cattle,

Bare-necked chicken and bleating goats.

They cannot cater for my Gunersy cattle

Or thorough-bred ponies,

On my ONE HUNDRED acre farm.

They would slaughter my Broilers one by one,

To feed their endless chain of relations.

Do you see that man,

Sleeping on the grassy patch,

Between the highway?

Do not include him in the exodus,

He guards my leafy home at night.

And this young man,

Carrying his ‘O’ level certificate,

Is a nephew to my wife’s cousin,

Let him stay on in the servants quarters,

Until I see the governor about him.

But do not forget,

my neighbours philandering cook,

I saw him touch my babysitter,

Let him go,

To impress the village beuties,

With his menu vocabulary.

Did you see me, at the recent fundraising?

I had on point five million shillings

From me and my friends,

In the blazing sun.

When we need these hecklers,

To shout and clap,

At the sound of every coin,

A bus will be hired,

To ferry their traditional dancers,

Jokers fand clowns.

References

1. Kenya Historical Biographies - Edited by King K., Salim A. East African Publishing house 1971

2. Zamani, a survey of East African History, edited by B. A. Ogot, East African Publishing House 1974

3. The Pan African, 12th December 1963 edition

4. Miller Charles, The Lunatic Express,, Ballantine Books, New York, 1973

Comments

Post a Comment

Your comments are very important to this blog. Feel very free to make your opinion known. We will respect it.